From the United States to Australia, cyberattacks targeting the power sector have surged dramatically. In Europe alone, such incidents doubled between 2020 and 2022—a trend unlikely to reverse as geopolitical tensions continue to escalate. Electricity is the lifeblood of modern societies, powering everything from homes and businesses to hospitals and national defense infrastructures. Yet this critical sector has become a colossus with feet of clay. While the integration of IT technologies into once air-gapped environments has enhanced demand-response efficiency, it has also exposed outdated legacy systems to unprecedented threats. Any disruption can trigger cascading effects across economies and societies, making the power industry a prime target in today’s tense geopolitical climate.

Within this complex, interconnected ecosystem, attackers often bypass sophisticated techniques. Instead, they exploit vulnerabilities patiently observing, waiting for the opportune moment to escalate their assaults. This article explores the power industry's blind spots, the reasons of OT–IT misalignment on security, and the emerging solutions to fill the gap.

(For the conceptual groundwork (attack surface growth, remote access pitfalls, and culture) see the primer that precedes this piece.)

The unnoticed transformation of the Electricity fairy

More diverse sources of energy and plants on the grid

The electrical grid is undergoing a profound transformation as diversity in energy sources reshapes its once‑predictable rhythms. Traditionally, electricity flowed along a simple, centralized path: large generators fed the network in one direction, operators relied on limited analog telemetry, and change occurred gradually enough to be managed through routine planning. That serenity ended when the grid became many‑voiced: the rise of distributed energy resources, such as solar PVs and wind panels to the power grid has updended the tradtion model by injecting variability and multiplying the number of small, decentralized production sites.

To keep such a dynamic system stable, communication networks that once carried only sparse operational signals now transport dense telemetry, remote‑control instructions, and software updates across fields, substations, control centers, and the cloud, enabling real‑time responsiveness to demand. Yet this expanded and increasingly digital ecosystem has exposed new weak points: in 2024, several hacktivist groups claimed attacks on small renewable energy facilities, often exploiting internet‑exposed management interfaces protected only by default credentials or simple passwords.

The stakes are higher in regions like Europe where interconnection is a feature, not an exception. Efficiency and balancing improve when power and data cross borders; exposure rises for the same reason. As the power grid expanses, dependencies and entry points multiply. And attackers pursuing destabilization reach for the most pivotal roles of this complex interconnected ecosystem: electrical substations.

The appearance of substations: a critical role and a weak spot

In a highly interconnected electrical network, substation are the conductors orchestrating a vast ecosystem of devices. This is where the fairy’s magic is measured, routed, and defended. Every new device, data path, and remote session is a seam that must be protected. Substations concentrate critical functions and heterogeneity. Yet, they are often remote, multi‑vendor, and maintained by mixed teams who depend on remote tooling.

A prolonged denial‑of‑service against telemetry and coordination layers can delay operator awareness, blunt automated responses, and starve control decisions of current data, turning a manageable disturbance into a wider incident if left unchecked. Hybrid operations that align cyber activity with physical disruption have shown how attackers amplify effects by striking both screens and steel. These are not merely technical problems; they are architectural and organizational tests of whether we can keep the fairy’s light from becoming someone else’s leverage. In a nutshell, the same interconnection that enables stable power supply in region can ripple outward if we neglect the seams where legacy hardware meets software‑defined control.

From policy to practice: what’s holding back?

Regulatory momentum has moved from guidance to accountability (i.e: NIS2) for power industry stakeholders. In Europe, the evolving framework translates directly into operational expectations for high‑impact entities in the power system. This is a call for IT to finally hear out OT’s needs.

Regulation is clear. Reality is not.

Controls once described abstractly are now expressed as concrete duties in the Network Cybersecurity Code: segment the network into zones and conduits, implement a Cybersecurity Management System, enforce strong identity and time‑bound access, and be able to evidence that these controls work in practice rather than on paper. But technology alone does not secure the grid; governance, culture, and day‑to‑day patterns do.

In the energy sector, cybersecurity codes call for minimum and advanced controls and for routine risk assessments that scope assets using the sector’s own impact lens so that isolation measures are enforced where they matter most. Supplier oversight is not optional; compliance verification and audits are part of the operational fabric. Zoning and isolation are expected to contain incidents and prevent them from spilling across systems, organisations, or borders. But none of this holds if the cultural foundations are misaligned. It’s like planning a holiday: before choosing the destination, you need to agree on what kind of trip you’re actually taking. If one partner dreams of rugged exploration while the other wants to stay by the pool, you won’t get far until you reconcile the vision. IT and OT face the same dilemma: the destination is shared, but the understanding of how to get there is often not.

Just ask them: the operational pain is real

In electrical substations, the people closest to the equipment feel the disconnect long before anyone else. Maintenance teams work under tight intervention windows with too many laptops and too many incompatible tools, expected to move fast while carrying the operational risk on their shoulders. Protection and control engineers live with the constant fear that a well‑intentioned IT change might ripple unexpectedly into automation logic or compromise protection schemes that keep the grid stable. SCADA (Supervision Control and Data Acquisition) and OT engineers see security rules built for office environments interfere with deterministic traffic that cannot tolerate latency, inspection, or unexpected filtering. And DSO (Distribution Systems Operators) or TSO (Transmission System Operators) field teams, who respectively deliver electricity to homes or move power across regions, operate under pressure where every minute can determine the scale of an outage. Yet they must navigate approval chains and processes designed for administrative comfort rather than emergency reality.

These teams do embrace security. But they struggle with a model that was never designed for the world they operate in: a world where uptime is non‑negotiable, where timing obeys physics rather than policy, and every action must serve continuity first.

What substation OT teams wished IT understood

For substation teams, availability and safety are non-negotiable—far more critical than patching schedules or data confidentiality. When IT enforces updates during periods of zero-tolerance downtime, or when change-management processes ignore the real-world behavior of protection relays, automation logic, or switching plans under electrical load, OT teams don’t feel supported, they feel vulnerable. The gap widens when IT tools fail to meet field realities.

Why they may bypass IT security measures

Corporate laptops often lack compatibility with legacy vendor software, outdated OS versions, serial communication drivers, or the proprietary tools technicians depend on. As a result, maintenance teams juggle multiple devices just to complete a single task. Security measures designed for office environments crumble in substations: blocked USB ports delay critical firmware updates, VPN tunnels disrupt local communications, endpoint agents interfere with serial traffic, multi-factor authentication fails in areas without signal, and misapplied segmentation rules accidentally block SCADA flows. These challenges reinforce the perception that "IT doesn’t get what we do"—especially when policies assume connectivity that doesn’t exist in remote or isolated substations.

At the heart of this divide lies a fundamental disconnect: IT rarely grasps the true cost of downtime in grid operations or the supply-chain complexities of managing decades-old, multi-vendor equipment under strict certification constraints. OT teams aren’t asking for weaker security. They’re asking for security that respects physics, timing, and the operational realities they navigate every day.

Bridging the Gap: Security Designed for OT Realities

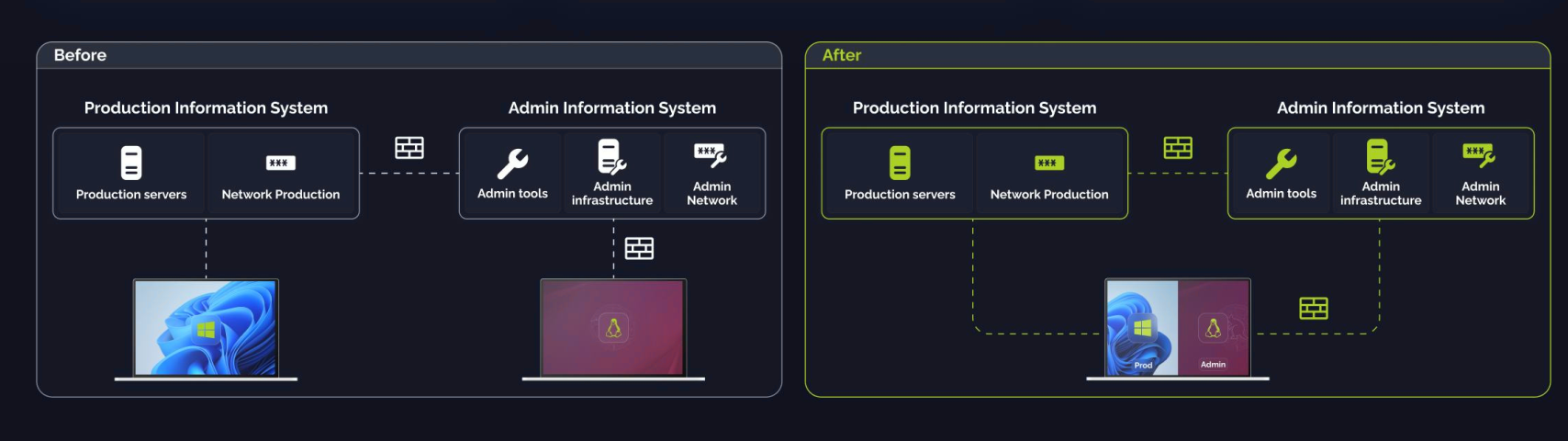

Convergence succeeds when security is designed to be used under pressure by teams whose first duty is to keep power flowing, not to debug a policy. Instead of multiplying hardware and exceptions, operators could explore emerging solutions. Nextgen virtualization would enable them to use a single machine that hosts several fully isolated environments. One environment would be for corporate tasks. The other would be for operations and remains bound to operational constraints (i.e: with a port being exclusively attributed to this environment). Each is strictly separated in permissions, settings; and access to the OT side is brokered. The result is simple in practice: engineers get the tools and speed they need; the organization gets segmentation that actually holds. This improves the company’s responsiveness, while giving maintenance teams more comfort and efficiency.

Nextgen virtualization solutions make IT security strategy practical for OT stakeholder rather than theoretical: multiple, strictly separated environments on one machine; brokered, auditable access; compatibility with high‑speed peripherals that maintenance teams actually use; and readiness that travels with technicians across decentralized networks, in a context where time and reliability matter most. Last but not least, this approach also eases supplier audits because every connection, tool, and action is knowable through the convergence of IT’s and OT’s SOC.

Conclusion: Security starts with empathy

From national transmission system operators orchestrating continental energy flows to distribution system operators managing the substations where electricity becomes reality, and the maintenance teams keeping aging equipment alive under relentless pressure convergence is what binds the grid together. It is the only path to a system that remains flexible, efficient, and resilient in the face of evolving challenges.

Yet convergence is not just about integration; it is about discipline. At KERYS, we understand that true resilience is built when architectures are designed to confine risk, when every access point leaves a traceable record, and when security solutions are shaped by the realities of substations and remote sites not the other way around.

The grid’s magic doesn’t happen by accident. It is sustained by the engineers, operators, and technicians who work tirelessly behind the scene to keep the lights on. We see you, we understand your challenges, and we’ve built a solution designed for those who power the world. Because the fairy’s light should never flicker.

Does it sound too good to be true? Let us show you how we do it.