Historically, OT environments prioritized availability and safety over confidentiality, which means many legacy systems were never designed for internet exposure. But IT–OT convergence has changed the game of industrial operations. Systems that were once isolated now share pathways with corporate IT networks, creating new entry points for attackers.

In this article, we’ll explore the risks of this convergence, the challenges induced for industrial operators, and the importance of human-centric approach of security in the era of IT-OT convergence.

How IT–OT Convergence Redefines Risk

The New Attack Surface and OT’s blind spots

Almost twenty years ago, industrial organisations entered the real-time data era. From power plants to factories, data-flow management has taken a central place of production optimization. This convergence of IT with OT is also an opportunity for organisations to improve OT’s cyber-resilience. In France, OT security and data optimization are the key benefits decision-makers expect from OT integration with IT. But convergence comes with increased risks as it expands the attack surface.

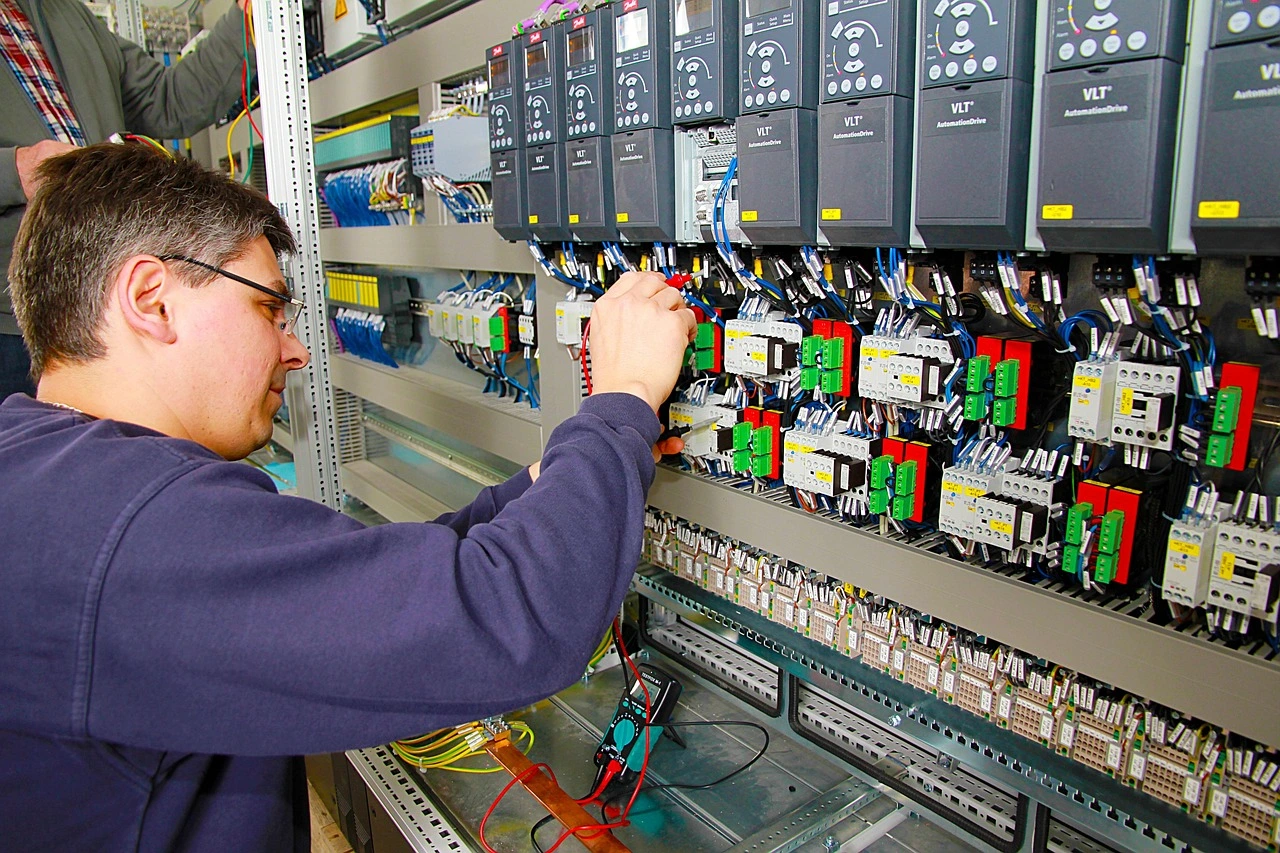

SCADA controllers and industrial devices, built for reliability rather than security, often lack encryption, authentication, and patching mechanisms—leaving organizations exposed. DCS legacy protocols designed for closed environments now operate in connected networks, creating vulnerabilities that attackers exploit with ease. As these systems connect to modern IT infrastructures, they meet IT’s dynamic threats like ransomware.

The risk is real for industrial operators. Ransomware campaigns increasingly targeting industrial control systems can force precautionary OT shutdowns and disrupt entire economies. The NotPetya attack, which spread through a trusted software update, crippled global operations and highlighted the blast radius of converged networks without proper segmentation.

Finally, supply chain compounds the problem. Industrial ecosystems rely heavily on third-party vendors for maintenance and updates, but this dependency introduces hidden vulnerabilities. Remote access, often implemented through traditional VPNs, can grant excessive lateral privileges, shared credentials, and unmonitored sessions.

These weaknesses turn vendor connectivity into a high-value target for attackers. Reports from leading OT security firms like Dragos consistently identify insecure remote access as one of the most common infiltration paths for ransomware and nation-state actors. Insider threats and poorly managed remote access amplify the danger, as vendors often bypass security controls for convenience, exposing organizations to lateral movement.

Regulatory Momentum: From Architecture to Accountability

To reduce the attack surface across OT ecosystems, the first major regulations of the 4.0 industry era focused on OT architecture regarding automated devices, IIoT and IT. In 2009, the IEC 62443 became a cornerstone, setting standards in automation and control systems. It enforces strict network segmentation between IT and OT zones, brokered access through a controlled gateway, and identity safeguards such as multi‑factor authentication, least privilege, and time‑bound authorizations. These controls address major aspects of OT security, from the governance and risk program requirements for asset owners (62443‑2‑1), to service‑provider obligations (62443‑2‑4).

Fifteen years later, NIS2 raised the bar in 2024 by making risk‑based security measures and supply‑chain oversight a legal obligation for essential and important entities, putting real consequences behind architectural choices. NIS2 emphasises on the adoption of robust security measures across essential and important sectors.

The practical path is to translate IEC 62443 into procurement language and vendor on‑boarding, make remote access brokered, auditable, and time‑limited, and require suppliers to evidence their patch cadence, component inventories, and incident processes. NIS2’s all‑hazards approach reinforces end‑to‑end accountability, pushing organizations to demonstrate—not just declare—that third parties meet the same bar inside operational environments.

The Human Factor

The gap between OT’s and IT’s technological philosophy

OT/IT environment in industrial organisations can be compared to a restaurant’s floor. The kitchen tiles meet the dining room wooden floor. Different material, different purposes, different constraints. In the same way, OT and IT have grown into two distinct worlds with their own security philosophies.

OT security architecture is deeply decentralized – spread across multiple geographically distant sites, each with their own process, systems, protocols. IT security is based on a centralized management approach. OT devices’ security needs to be evaluated for 1 year minimum before use while IT software can run with continuous patching to face to tackle the evolving threats landscape. Compatibility adds another layer of complexity: IT solutions rarely integrate smoothly with industrial control systems such as SCADA or DCS.

To bridge this technological gap and remain compliant, many industrial organizations have resorted to a workaround: giving operators several computers—one for corporate tasks, one for operations, one for administrative access. OT teams, already under pressure, end up juggling multiple devices. But technology alone cannot secure converged environments.

Just as a restaurant uses reducer strips to create a seamless connection between two different floor types, organizations need a unified security mindset that connects IT and OT. Both teams must share responsibility for resilience. This requires policies designed around operational realities: Bridge feature, granular access controls that support maintenance without disrupting processes, port attribution to dedicated (virtual) machines, and compatibility with high‑speed data transfer protocols.

Introducing new security protocols without disrupting critical processes requires careful planning and empathy. Traditional awareness programs and solutions often fall short because they fail to address the operational realities of industrial environments. Instead, they must be contextual, demonstrating how they contribute to safeguarding uptime rather than threatening it.

The missing link to bridge the gap: cultural alignment

When converging theses OT/IT ecosystems, organizations usually focus on the technical aspects selecting tools, connecting systems, and demonstrating security benefits. What is overlooked is how people will work together once these systems meet. Approval processes become bottlenecks, and when IT solutions feel complex or incompatible, OT teams bypass them. These are professionals working under constant pressure to maintain uptime. Expecting flawless compliance without addressing perceived value is unrealistic.

The real foundation of successful convergence is cultural alignment. According to the NXO report, only 30% of IT and OT teams share a common vision of security—a disconnect that significantly slows convergence. Without shared understanding and priorities, even the strongest architectures struggle to take root.

The human dimension often determines whether security measures succeed or fail. Considering the human dimension is about understanding each side’s vision, and priorities. In that latter, IT and OT teams operate under fundamentally different priorities: IT focuses on confidentiality and rapid patching, while OT emphasizes uptime and safety. For OT operators, the fear of downtime is real. Every minute of halted production can translate into significant financial loss.

The human dimension often determines whether security controls succeed or fail. IT and OT teams operate under fundamentally different imperatives: IT prioritizes confidentiality and rapid patching, while OT prioritizes safety, predictability, and uninterrupted operations. For OT operators, downtime is not an abstract risk but an immediate operational and financial threat. This is why cybersecurity initiatives are sometimes perceived as disruptive rather than protective.

Behavioural economics helps explain such resistance to change. Loss aversion, status quo bias, and low perceived value lead operators to be suspicious about some IT initiatives. Some argue that most well-known OT attacks started on IT networks (i.e.: colonial pipeline attack), making IT responsible for exposing them to these threats. Other operators believe their automates hardware security is sufficient...until an incident occurs.

The perceived safest option is usually the one we’re more familiar with. That’s the same reason why one’s grandparent has always refused to get a microwave. This is also why some customers would rather eat in a 3.2-rated McDonald’s (especially abroad) than a 4.7 rated unknow restaurant. They know what to expect from McDo, whereas there’s still uncertainty about the other restaurant. In a nutshell, most operators simply fear change, and the uncertainty it usually brings.

Overcoming these biases means reframing security as a guarantee of uptime and operational continuity—not as an IT mandate. Clear communication, leadership engagement, and incentives for compliance can transform security from a perceived burden into a shared value. Otherwise, the cultural gaps will create blind spots where security controls are delayed or ignored.

Conclusion: Securing the last frontier of cybersecurity

IT–OT convergence is no longer a future trend. It is today’s reality, reshaping the way industries operate and exposing them to unprecedented cyber risks. The expanded attack surface, legacy vulnerabilities, and supply chain dependencies demand more than incremental fixes. They require a true shift of mind regarding industrial devices, and hardware security in general. This change of paradigm is also an opportunity to eventually address and close the cultural gap between OT and IT.

To do this, industrial organisations are called to base their resilience strategy on empathy, communication, and a deep understanding of the human context behind each stakeholder. Security is not just a technical challenge but a human one. At KERYS Software we believe security is also about simplicity and practicality in the end-users’ context. There’s no point in having the most secure solution or protocol if users bypass it because of its complexity. That’s why we built a solution that makes security practical for end-users, while enabling compliance and operational continuity without sacrificing efficiency.

Does it sound too good to be true? Let us show you how we do it.